The return of ground effect aerodynamics in Formula 1 has been one of the most significant technical shifts in recent years, and its evolution continues to shape the future of the sport. As the FIA prepares for the 2026 regulation overhaul, the focus remains on enhancing wheel-to-wheel racing and improving overtaking opportunities. The upcoming changes promise to redefine how cars interact with dirty air and how drivers can attack or defend positions on track. But what exactly will these adjustments mean for the spectacle of F1 racing?

Ground effect, reintroduced in 2022, was meant to reduce the turbulent wake behind cars, allowing following drivers to stay closer through corners. While it succeeded to some extent, the 2026 regulations aim to refine this concept further. The new rules will likely tweak the underfloor designs, potentially increasing downforce generated by the diffuser while minimizing reliance on upper-body aerodynamics. This shift could make the trailing car less susceptible to losing grip when chasing another, creating more consistent performance in dirty air.

One critical area of development is the balance between mechanical grip and aerodynamic dependence. Current cars still lose considerable downforce when running closely behind another vehicle, particularly in high-speed corners. The 2026 regulations may address this by mandating simpler front and rear wings, reducing their sensitivity to turbulent airflow. If executed well, this could allow drivers to carry higher cornering speeds when following, setting up better overtaking opportunities on the following straights.

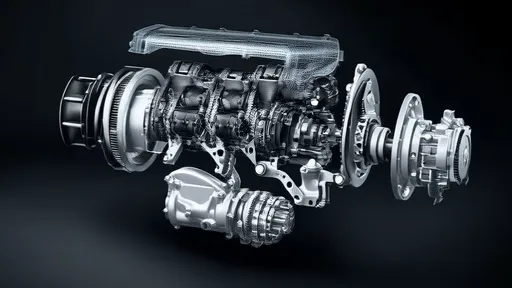

The power unit revolution coming in 2026 will also play a crucial role in changing overtaking dynamics. With engines becoming more energy-recovery focused and potentially producing over 50% of their power electrically, acceleration out of corners may become more dramatic. This could lead to stronger slipstream effects on straights, as the sudden bursts of electric power might create larger speed differentials between attacking and defending cars. However, the exact impact will depend on how the FIA balances energy deployment rules to prevent excessive battery-powered "push-to-pass" systems from making overtakes too artificial.

Another fascinating aspect of the 2026 changes involves tire design. Pirelli is working on new compounds that could better withstand the stresses of close racing. Current tires often overheat when cars run in dirty air for prolonged periods, forcing drivers to back off. If the 2026-spec tires can maintain more consistent temperatures in turbulent conditions, we might see longer sustained battles where drivers can pressure each other lap after lap without destroying their rubber.

The weight of the cars remains a concern, however. Despite efforts to make vehicles lighter, the 2026 machines might still tip the scales at nearly 800kg due to heavier batteries and safety structures. This could affect how quickly cars can change direction when dueling and how late they can brake into overtaking zones. Some engineers suggest that the FIA might introduce revised brake-by-wire systems to compensate for the increased mass, potentially giving drivers more tools to attempt daring overtakes.

Perhaps the most intriguing potential change lies in active aerodynamics. While ground effect remains passive, the 2026 rules might introduce movable aerodynamic components that adjust automatically based on following distance. Such systems could theoretically maintain optimal downforce regardless of whether a car is leading or chasing, revolutionizing how drivers approach overtaking. However, this remains controversial, as purists argue it would remove an essential skill element from racing.

As teams begin to develop their 2026 challengers, simulator work is already revealing how these changes might play out on track. Early data suggests that the combination of refined ground effect and reduced aero sensitivity could create racing where drivers can follow within 0.3 seconds through high-speed corners, compared to the current 0.7-second threshold before significant downforce loss occurs. This tighter performance window might lead to more position swaps through technical sections rather than just on straights with DRS.

The DRS system itself faces an uncertain future in this new era. Originally introduced to compensate for overtaking difficulties, its role might diminish if the 2026 cars can follow closely naturally. Some proposals suggest replacing it with a more subtle overtaking aid or removing it entirely to test the effectiveness of the new aerodynamic philosophy. Such a move would represent a major shift in F1's approach to facilitating overtaking after more than a decade of DRS-dependent racing.

Driver feedback on these impending changes has been mixed. While most welcome any improvement in racing quality, some express concerns about cars becoming too easy to drive closely, potentially reducing the skill required to execute clean overtakes. The challenge for regulators is finding the sweet spot where overtaking becomes possible but still requires genuine driver skill and bravery to complete successfully.

As the 2026 season approaches, all eyes will be on how these technical evolutions translate to on-track action. Will ground effect's refinement finally deliver the close racing F1 has promised for years? Can the new power units create exciting new overtaking dynamics without artificial aids? The answers to these questions will shape Formula 1's competitive landscape for years to come, potentially creating a golden era of wheel-to-wheel racing or exposing new challenges in the perpetual quest for the perfect overtake.

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025